The Fallopian Tubes

The only female sex organs whose only biological purpose seems to be ...

reproduction

Dr. Nelson Soucasaux , Brazilian gynecologist

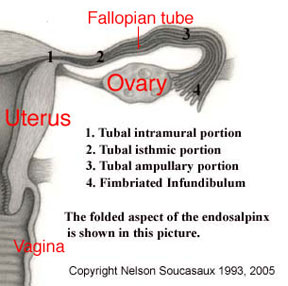

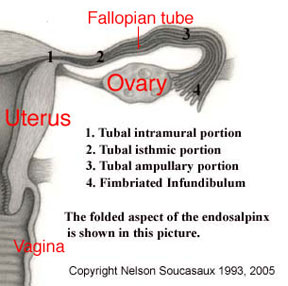

Despite their beauty and delicacy, of all the female sexual organs the

Fallopian tubes [see drawings, below] are the only ones whose only biological

purpose seems to be ... reproduction (at least as far as we know). From

the point of view of interdisciplinary studies, unfortunately it is also

very difficult to find archetypal references to these organs in mythology.

Both from the structural and functional points of view, the Fallopian tubes are

extremely delicate organs and, therefore, highly vulnerable to all kinds

of aggressions, mostly infectious/inflammatory processes that easily may cause

their obstruction and/or impairment of their movement and function, resulting

on infertility or tubal pregnancies.

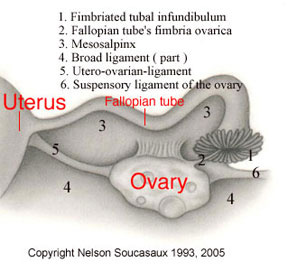

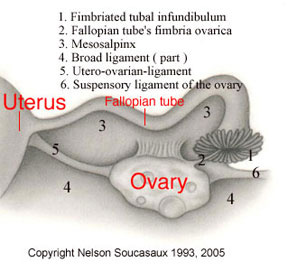

In almost all their length, each Fallopian tube is formed by a thin

cylindrical muscular layer internally lined by a folded mucosa named the

endosalpinx. From the point of their uterine insertion on, the tubes follow

their own way towards the ovaries. Throughout their path, they run along

the broad ligaments, which they are attached to by means of peritoneal folds

named mesosalpinges.

Three portions can be distinguished in the Fallopian tubes: the intramural,

the isthmic and the ampullary.

The intramural portion consists of an extremely narrow canal that crosses

the uterine wall for opening into the uterine (endometrial) cavity.

The isthmic portion starts just at the point where the tubes emerge from

the uterine upper angles; it is less narrow than the intramural and, as

it approaches the ampullary portion, it gradually widens. (There is no sharp

distinction between the isthmic and the ampullary portions.) As to the ampullary

portion, Dr. Frank Netter observes that it is "... tortuous and gradually

widens toward the outer end. It terminates in a fimbriated infundibulum

which resembles a ruffled petunia or sea anemone. On the fimbriae, the fimbria

ovarica is grooved and runs along the lateral border of the mesosalpinx

to the ovary."* Further on: "Contraction of the longitudinal muscle

fibers of the ovarian fimbria brings the infundibulum in close contact with

the surface of the ovary."* This seems to be the main mechanism responsible

for the "embrace" given to the ovary by the tubal infundibulum

at the moment of ovulation, with the purpose of capturing the oocyte [egg]

that is being expelled.

|

|

The tubal muscular layer is formed by an intricate arrangement of circular

and longitudinal smooth fibers, facilitating the propagation of the tubal

peristaltic waves towards the uterus. The tubal circular muscle fibers communicate

with the double system of spiral fibers which, symmetrically entwined and

interlaced around the uterine cavity, constitute most of the myometrium

(the uterus's powerful muscular layer). The fact that the uterine contractile

waves originate in the upper angles of this organ, just at the insertion

of the tubes, is due to this communication between the tubal and uterine

circular and spiral smooth muscle fibers.

The endosalpinx is characterized by the formation of an extremely intricate

system of longitudinally arranged folds. Whereas in the intramural portion

these folds are sparse and small, from the isthmic portion on up to the

infundibulum they gradually become more and more numerous, extremely branched

and arborescent. As Netter observes, in the ampullary portion the configuration

of this endosalpinx folding acquires labyrinth-like features.*

The endosalpinx is lined by a single-layered columnar and ciliated epithelium,

basically formed by two kinds of cells: the ciliated and the secretory ones,

which alternate irregularly along the mucosa. These cells are sensitive

to the ovarian hormones and, according to Ham, their heights, relative or

absolute, vary in accordance to the several periods of the menstrual cycle.**

Netter observes that "... the height of tubal epithelium reaches its

peak during the period of ovulation and is lower during menstruation."*

According to this author, the number of secretory cells becomes greater

along the luteal phase of the cycle.*

Just like the peristaltic movements of the tubal muscles, the ciliar

movement of the endosalpinx (which is due to its ciliated cells) is also

directed towards the uterus. When pregnancy occurs, both of them aim to

carry the fertilized egg to the uterine cavity. On the other hand, the secretory

cells are in charge of supplying nourishment to the egg during this transportation,

which usually takes about 5 to 7 days.

As I have observed in my article "Fundamentos para o Estudo das

Influências Neurovegetativas em Ginecologia" ("Basis for

the Study of the Neurovegetative Influences in Gynecology")***, regardless

of the fact that the tubal motility is fundamentally stimulated by the estrogens,

the simultaneous existence of a co-ordinating activity on the part of the

vegetative innervation of the tubes in this process seems to be evident.

During ovulation, even knowing the crucial role played by the pituitary

LH ovulatory peak in helping the process of oocyte capture by the Fallopian

tube and also the increase in the tubal motility caused by the high estrogen

levels of this phase of the cycle, I still believe it is hard to explain

only endocrinally the authentic "embrace" given in the

ovary by the fimbriated tubal infundibulum in order to so perfectly capture

the oocyte. As already mentioned, it seems to be the contraction of the

Fallopian tube's ovarian fimbria that makes the tubal infundibulum

come closer to the ovary and finally surround it with its fimbriae. In this

way, the possibility of a subtle neurovegetative co-ordination of this extremely

intricate process, as well as of the tubal peristaltic waves that aid to

carry the fertilized egg towards the uterus, must also be seriously considered.

* Netter, F.H. - "The Ciba Collection of Medical Illustrations

- Vol 2, Reproductive System" - USA, 1954.

** Ham, A.W. - "Histology" - J.B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia,

1965.

*** Soucasaux, N. - "Fundamentos para o Estudo das Influências

Neurovegetativas em Ginecologia" ("Basis for the Study of the

Neurovegetative Influences in Gynecology") - in: Jornal Brasileiro

de Medicina, vol 57, nº 4, October 1989.

The text above is an excerpt from my book "Os Órgãos

Sexuais Femininos: Forma, Função, Símbolo e Arquétipo"

("The Female Sexual Organs: Shape, Function, Symbol and Archetype"),

published by Imago Editora, Rio de Janeiro, 1993. For information on the

book, see page http://www.nelsonginecologia.med.br/orgaos.htm

, at my web site www.nelsonginecologia.med.br

.

Copyright Nelson Soucasaux 1993, 2005

_______________________________________________

Nelson Soucasaux is a gynecologist dedicated to clinical, preventive

and psychosomatic gynecology. Graduated in 1974 by Faculdade de Medicina

da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, he is the author of several

articles published in medical journals and of the books "Novas Perspectivas

em Ginecologia" ("New Perspectives in Gynecology") and

"Os Órgãos Sexuais Femininos: Forma, Função,

Símbolo e Arquétipo" ("The Female Sexual Organs:

Shape, Function, Symbol and Archetype"), published by Imago Editora,

Rio de Janeiro, 1990, 1993. He has been working in his private clinic since

1975.